Iaido/Kendo in Norwich

Kendo has been practiced in Norwich for over 60 years. SEIKUKAN KENDO DOJO has been in existence since 1982.

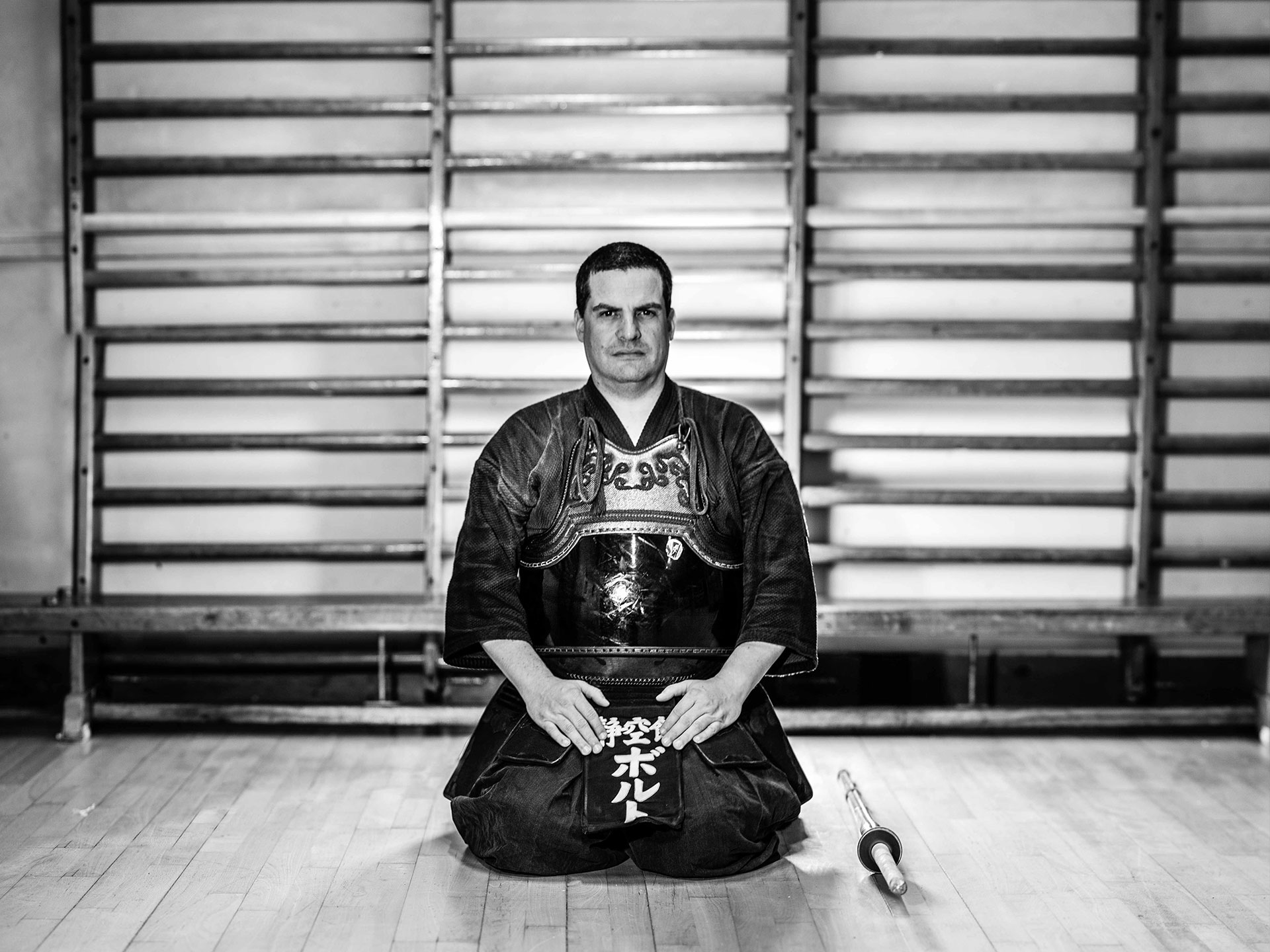

Paul Holmes has been the instructor in Kendo and Iaido for over 35 years.

There are two assistant instructors, (Wayne Bolt KENDO) (Sally Barter IAIDO AND KENDO)

There is a grading structure in place and new members will be required to become members of the British Kendo Association, (small fee applicable, this covers for insurance).

Contact Us

If you have an inquiry or wish to ask any questions please feel free to fill out the contact form opposite.

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

New classes will consist of the following:

IAIDO

Seitei Iaido

(taken from multiple schools and is a grading requirement)

Koryu

(Muso Shinden Ryu)

Tameshigiri

(cutting targets)

KENDO

Kendo fencing

(long sword)

Tan Kendo fencing

(short sword)

Kendo Kata

New classes will be for beginners advancing to intermediate and for seniors.

Iaido

Iaido [ee-eye-do] (居合道) is the art of drawing a Japanese sword from its scabbard to obtain advantage over an opponent. The sword is drawn to defend one’s self, to control or to kill an enemy in the most efficient way. Iaido as we know it today probably began with Iizasa Choisai, the founder of the Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu. Hayashizaki Jinsuke Shigenobu (1542-1621), like Iizasa Choisai, is reputed to have received a divine inspiration, which led to the development of his art.

Nowadays Iaido represents the intrinsic form of Japanese Budo and is used as a form of mental and physical discipline, emphasising correct technique and form and character development. The study of Iaido encourages strength, balance, co-ordination and suppleness.

Since Iaido is practiced with a weapon, the training is based on kata (set forms). Each form represents a different combat scenario. By practicing in a repetitive manner the practitioner learns and develops technique. Techniques are highly refined, simple and direct. A beginner’s performance reveals lack of control and rigidity while a master’s appear effortless and natural.

Stages in training

1. Keiko. This means quite simply training or practice. This is the stage during which the essential movements are perfected by slow repetition, by breaking the kata down into its component parts, by understanding how the techniques work in a fighting situation. With this practice the swordsman begins to understand the principles of Metsuke (correct use of the eyes), Seme (pressing or pushing) in order to control the opponent, of Maai (combative distance) and Ma (timing). This study takes about five years of regular practice. Overlapping with it, from about the third or fourth year, the swordsman will begin the practice of Tanren.

2. Tanren means to forge in the same way that a sword blade is forged, with hard work, and sweat, and many hours of dedication, folding together the hard and soft elements in the body, mind, and movement just as the sword gains its strength out of hard and soft steel. The student increasingly practises without concern for the correctness of the movements (though they must remain correct and effective) and repeats the kata uninterrupted with a feeling of Shinken Shobu (a fight to the death with a real sword). During this phase posture improved, movements become more natural, techniques become more effective because timing is better controlled and less predictable. As confidence increases and Kigurai (bearing, demeanour) develops, training moves into the phase called Renshu.

3. Renshu. Ren means to polish, to perfect by continued practice of both keiko and tanren. It also means to polish the spirit and character through the requirements of detail and interpretation. To demonstrate a compassionate nature that can pass on knowledge without egotistical pride and arrogance. This leads to the award of Renshi meaning a person whose performance and character is polished by training. This grade is not awarded below the rank of 6th Dan and is only available from the All Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR).

After this stage the actions become slower and softer, appearing to a bystander to be less effective-but the technique comes from refined efficiency, not using force-until the moment the sword is actually cutting, remaining relaxed in body but constantly aware and prepared in mind. Only after leaving all of these stages in the past and demonstrating the simplicity of the correct action and knowing all of these stages by direct experience can the student who has by now gained 7th Dan receive Kyoshi (teacher grade) from the ZNKR.

The Curriculum

After learning basics of how to hold a sword and cut with it the beginner is gradually introduced to the twelve kata of the All Japan Kendo Federation. These forms were developed in the 1960′s and 70′s as a national and later, international, standard for teaching, grading and competing. The moves are derived from the most popular of old styles (koryu), and, although they represent basic study in preparation for koryu practice, they continue to be the forms through which instructors and sensei demonstrate basic principles at all levels. Following these there are old style kata. Most common in the UK and Japan are Muso Shinden Ryu and Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu, both of which are off-shoots from the Muso Shinden Jushin Ryu Batto Jutsu mentioned above.

These schools have five sets of kata, three of one-man sword drawing (Iaido) and two of two-man techniques (ken jutsu). As the student progresses through the sets, the range of interpretations widens, so that whereas the beginner had a very strict defined set of moves, the more advance student is able to imagine Kasso Teki (his imagined enemy) moving or acting differently, and adapt the kata accordingly. Similarly, with the two-man kata the student (Shidachi) must learn to cover his weak openings (Suki). If he does not the teacher (Uchidachi) will show him where he is weak by attacking other than as prescribed by the kata. This is the start of how we learn to become prepared for any eventuality in Iaido.

The Equipment

Iaido is normally practised wearing a hakama (baggy pleated trousers) and keiko gi (training jacket). An iai obi (sword belt) is worn under the hakama cords to hold the sword in place. The hakama is usually black or dark blue, and the keikogi matching colour or white. A white hakama can be worn, but this is usually considered to be summer dress. There is no indication of grade by any means in the costume. A zekken is worn on the left chest indicating your name and club, or country when attending international events. The swords used range from bokuto (wooden sword) for beginners, to iaito (plated alloy blunt practice swords) for the more experienced. Please don’t turn up to a dojo for your first lesson with a sharp sword and expect to be allowed to use it! The dojo needs to be an area of plain floor, preferably wood, without mats, and with sufficient head-room to swing the sword. For individual practice I find a squash court to be ideal.

The format of a practice After warming up and stretching the practice begins with opening etiquette consisting of kamiza ni rei (bow to high side), sensei ni rei (bow to the teacher) and to rei (bow to the sword). Then follows suburi (cutting action practice) and kihon including Chiburi (blood shaking action) and Noto (re-sheathing). Depending on the size and level of the class further techniques derived from the kata may be practised individually before the kata practice begins. The kata practice often begins with the teacher explaining points to be practised, either to the class as a whole or to groups at different grades as appropriate. Then follows either a formal practice in which everyone performs together, following the timing of the dojo leader, or a free practice when everyone performs the kata in their own time while the instructor wanders from student to student correcting points as necessary. At the end of the session everyone performs the finishing etiquette together.

Kendo

In the Middle Ages, Ito Ittosai Kagehisa developed the style that forms the basis of present day Kendo. Kendo historians estimate that there were more than 200 different sword schools and styles by the end of the sixteenth century.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, serious thought was given to developing armour to protect trainees from permanent disability, or even death, during vigorous training. Known then as ‘Kenjutsu’, the art of Kendo became more popular with the improvement of protective armour, the simplification of many of the vast number of traditional techniques and the acceptance of rules of conduct within the fencing hall.

From Kenjutsu developed Kendo, using the bamboo sword (‘shinai’) to replace the metal sword, and thus allowing the free practice of swordsmanship. The shinai is made of four splints of bamboo held together at one end, with a tubular leather handle slid over the splints and a leather cup at the other end. The shinai weighs around 500 grams, and various basic cuts and thrusts are made repeatedly to build up speed and stamina.

To focus concentration and to aid correct breathing a shout, or ‘kiai’, is made on the completion of each strike. When practising Kendo, padded armour (traditionally made of bamboo and cotton) is worn over the customary dress of the samurai.

To score, a good cut must be delivered to well-defined targets (the top of the head, right wrist and the breastplate) using the upper third of the shinai. Thrusts to the throat may be made with the point of the shinai. All the targets are well protected by the armour.

First impressions of Kendo are of a noisy, aggressive and violent full-contact martial art. Kendo is certainly dynamic, but a little study will soon reveal a high level of skill and concentration, together with a grace and physical agility that any choreographer would appreciate.

Students are from all walks of life and of any age, and women train on equal terms with men.

Kendo may be safely practised by men, women and children of all ages, and the type and level of practice may of course be adjusted to suit each pupil. The most senior Kendo teachers in the BKA are 7th Dan, with several 6th and 5th Dans who train in various parts of the country.

If you are starting kendo, you may also be interested in this free download: Kendo Beginners Guide – a new and practical introduction for kendoka of all levels, by Terry Holt sensei.

In 1975 the All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF) developed then published ‘The Concept and Purpose of Kendo’ which is reproduced below.